China's Domestic Fruit Industry and What it Means for Imports [1]

Submitted by Dan Siekman [2] on

Lu Fangxiao, President of the China Fruit Marketing Association

In separate presentations at last month’s PMA Fresh Connections: China conference, Mau Wah Liu, Chairman of Joy Wing Mau Group and Lu Fangxiao, President of the China Fruit Marketing Association, both had a lot to say about the corner that China’s domestic fruit industry has backed itself into.

At the core of the domestic industry’s troubles is what Liu calls, “conflict between supply and consumption of Chinese fruit industry: the growing demand for high quality fruits and relatively backward supply development.”

According to Lu, “the domestic fruit industry has moved from facing supply shortages to now facing a structural contradiction in which supply exceeds demand while supply is simultaneously insufficient.”

Basically, Chinese production is growing steadily, but too much of the overall supply is low grade specimens of a narrow selection of species and varieties. For example, Fuji apples, Asian pears, bananas, red globe grapes, bananas, and melons.

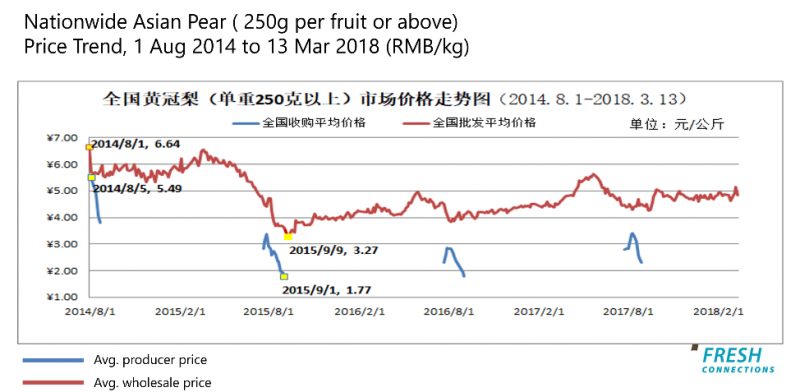

Meanwhile, Chinese consumers are more and more craving what Lu calls, “fruit that is premium-quality, differentiated, safe, organic, branded and/or high value.” This means that although demand for fresh fruit is increasing in China, prices for many fresh fruit crops have slid in recent years and failed to recover.

This situation may have helped boost imports. Lu noted that since 2010, when China was exporting more fruit than it was importing, imports and exports became roughly equal for several years, and now China is importing more fresh fruit that is it exporting, both by volume and value. “Chinese fruit’s price advantage in export markets has weakened, and domestic consumers’ demand for premium and safe fruit from outside China has grown,” said Lu.

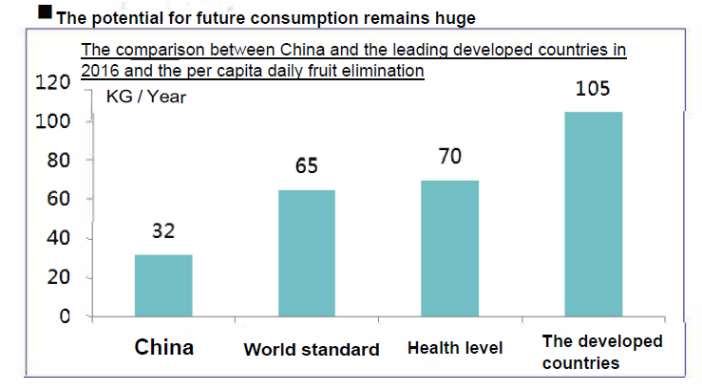

Joy Wing Mau’s Liu outlined a number of reasons to be confident for international suppliers of imported fruit to the China market, as well as some potential dangers. On the good side, he highlighted that imports still make up a low proportion of China’s overall consumption, and per capita consumption of fresh fruit in China remains low compared to other countries in the world. This means there is plenty of room for growth.

But Liu also pointed out that although 2017 was a good growth year, fresh fruit import volume and value fell in 2016. Averaged over the past three years, fresh fruit imports into China are actually growing at a slower rate than China’s GDP. This is a possible source of concern for the import market: if growth is sluggish at a time when domestic supply is not aligned to market demands, what might happen if the quality of domestic production improves?

And Liu believes this realignment in production is already happening to an extent, and will accelerate over the next ten years. As examples of Chinese producers starting to realign production to match changing demands of domestic consumers he cited progress in domestic kiwifruit breeding and production, branded citrus like Chu oranges, table grapes, and increasing domestic production of blueberries and raspberries, which were historically not grown in commercial quantities in China.

It is also widely held to be true in agricultural circles in China that the government is strongly committed to developing the domestic agricultural industry, including more emphasis recently on commercializing research outcomes.

Overall, both Lu and Liu predicted that rising standards of living and changing consumer trends are setting up China’s fruit market for a “golden era” of growth and development over the next decade—with bright opportunities for both international and domestic producers who can overcome key challenges and adapt to consumers’ demand for differentiated and high-quality fruit. “If you have good products, price is not a problem,” said Liu “The middle class is willing to play a premium price for premium quality products.”